wral.com

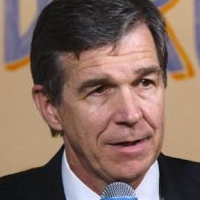

Roy Cooper

Sept. 11, 2016

“I honestly don’t understand not only how the Attorney General’s Office felt it was necessary to fight us through a full week of hearing in this case, but how they could stand up at the end of that hearing and say they thought Johnny should stay in prison.

“That is not a minister of justice. A minister of justice should be objective enough to evaluate the evidence in a fair way and there was no way anybody could look at the evidence that came out in that hearing and say Johnny Small should be in prison.”

– Chris Mumma of the N.C. Center on Actual Innocence, quoted in “Johnny Small free after murder charge dismissed” in the Wilmington Star-News (Sept. 8)

I would’ve expected, before my apprenticeship on the exoneration watch, that district attorneys would be less willing to having their fingers pried loose from wrongful convictions than their allies in the attorney general’s office. It’s the DAs, after all, who have to ‘splain their misfeasance to the voting public.

But this often seems not to be the case, as exemplified by Assistant AG Jess Mekeel’s misplaced concern for “the stability and reliability of our justice system.”

How much of this institutional resistance to exoneration owes to a tradition of prosecutorial blood-brotherhood? And how much springs directly (if not via email) from Attorney General Roy Cooper?

If Cooper took heed of Mumma’s thoughtful plea for “more cooperation between prosecutors and defense attorneys in their efforts to achieve justice,” evidence of it has yet to surface.

![]()